What Do We Mean When We Talk About 'the Urban'?

In the summer of 2023, El País published “Hip Hop Hegemony,” an article by Xavi Sancho that highlighted the contemporary relevance of this cultural movement. “For quite some time now, everything is hip hop, and what isn’t hip hop either comes from it or is heading in that direction,” he wrote . For those of us who have been consumers and participants in this culture, it was with a sense of pride that we read these words in a mainstream newspaper finally offering some recognition to a movement that today holds significant sociocultural influence.

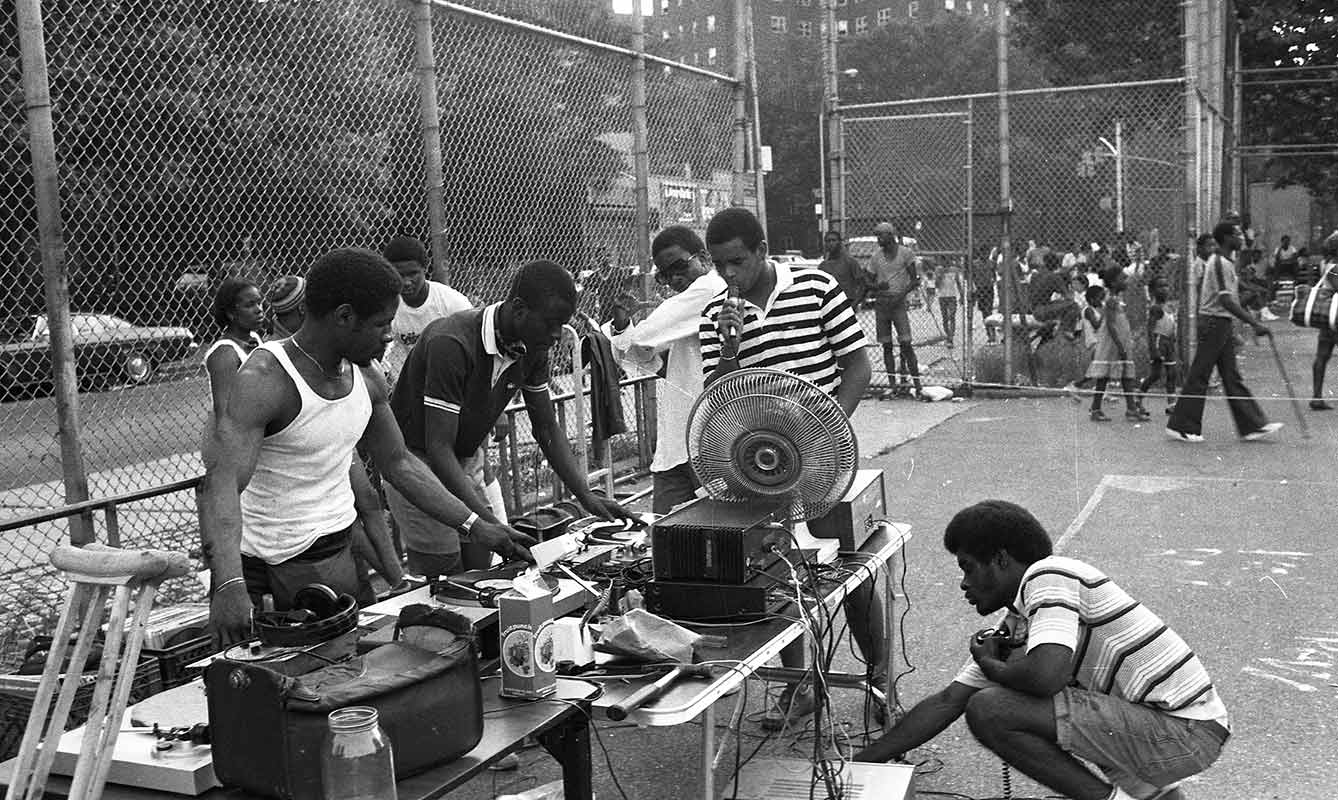

Photograph “G Man. Park Jam in The Bronx” By Mr Henry Chalfant from https://www.henrychalfant.com/

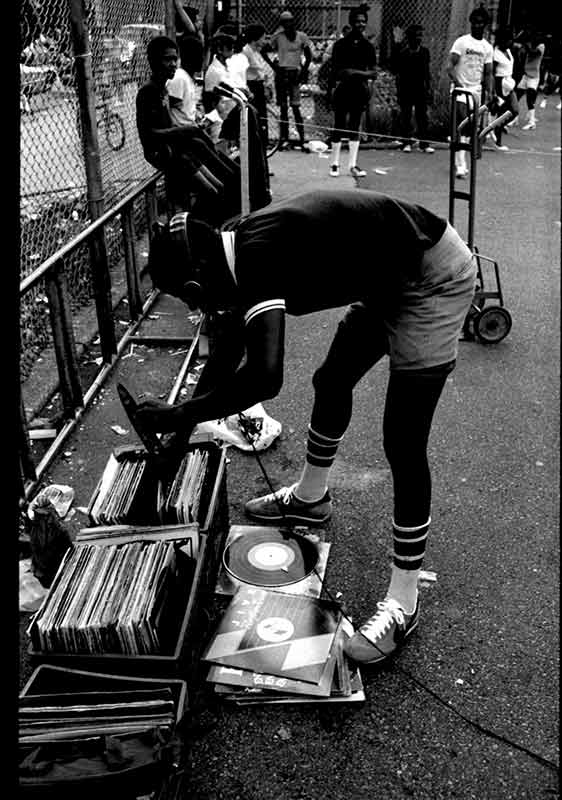

Photograph “B Boy on Broadway & 96th St.” By Mr Henry Chalfant from https://www.henrychalfant.com/

Yet, we continue to see how many media platforms refer to this culture using the term urban, commonly grouping under the label “urban music” a wide array of genres and subgenres that originate from hip hop culture, such as rap, trap, among others—often while committing fundamental conceptual inaccuracies.

Why are all these genres placed under the umbrella of “urban”? What characteristics do these forms of music possess that link them to the urban environment, and not others? Are rock, pop, or techno somehow non-urban forms of music? To understand the term’s origins, we must go back to the first-time rap or related genres were referred to as “urban music.” In the 1970s, Frankie Crocker, a DJ and radio host on New York’s WBLS-FM, coined “urban contemporary” to describe a diverse mix of music rooted in and blending genres such as soul, R&B, and disco.

These musical variants were popularly known as “Black music,” as they emerged within African American and Latin communities in the United States—specifically in the Bronx, New York. However, advertisers on stations like WBLS-FM often refused to associate their commercial spots with music labeled as “black.” In response, the term “urban contemporary” was adopted to “sanitize” or rebrand this new musical current to circumvent the racial biases and censorship that prevailed in the radio industry at the time.

Fifty years later, terminology persists, though some media platforms and institutions have begun to move away from it. A notable example is the U.S. National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences, which in 2020 eliminated any reference to “urban” in Grammy Award categories related to hip hop and R&B. The disappearance of the term reflects a broader effort to reorganize an industry that had long used “urban” to isolate Black artists from broad categories—often synonymous with pop.

Still, why was the urban chosen term to rebrand this genre in the first place? And why has it endured for so long, crossing so many cultural and geographic boundaries? The concept of “urban music” was initially tied to a genre consumed primarily in the streets—that is, the street is understood as a cultural ecosystem for a social group excluded from the formal structures of music creation, production, and dissemination. Rap—the precursor of what came to be labeled as “urban music”—was not originally produced in recording studios. It was not performed in venues designed for such events, like clubs or concert halls, nor was it distributed through mainstream radio stations.

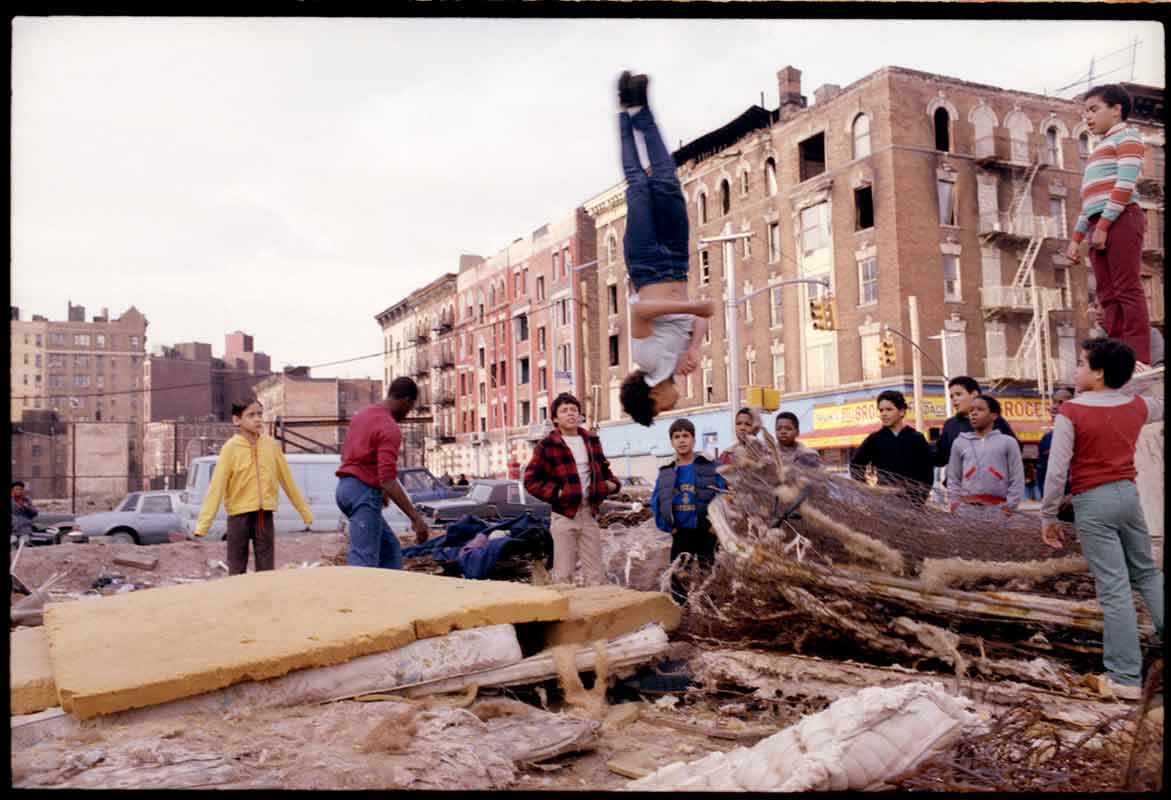

Photograph “Park Jam in The Bronx” By Mr Henry Chalfant from https://www.henrychalfant.com/

Rap emerged in the urban environment: in public spaces and the ruins of burned-out buildings. The street was the meeting place and site of cultural production for African American and Latin communities who lacked access to the infrastructure necessary to develop these activities under more favorable conditions. In this way, hip hop instigated an unprecedented transformation in urban life. It became the social network that, in the 1970s and 1980s, connected the residents of the Bronx. To grasp the depth of this culture’s impact, we might recall the words of scholar Tricia Rose:

“In the postindustrial urban context of dwindling low-income housing, a trickle of meaningless jobs for young people, mounting police brutality, and increasingly draconian depictions of young inner-city residents, hip hop style is black urban renewal”.

Thus, hip hop is not only defined by its various cultural products—rap, DJing, MCing, breakdancing, graffiti, and more—but also by its status as a form of urbanism that develops its rituals of appropriation and use of public space.

One of the primary reasons for the emergence of hip hop lies in its capacity to reinterpret architecture and the city in ways that diverged from their originally intended functions. These new protocols for inhabiting the urban environment have remained a constant as hip hop has expanded to other geographies—such as Europe, and specifically Spain. But the replication of these codes is not merely a feature of this cultural transmission; it is also a necessary condition for the genre’s successful evolution.

Photograph “Mattress Acrobat, Hoe Avenue, the Bronx” By Mr Henry Chalfant from https://www.henrychalfant.com/