We believe it is important that architecture should begin with dialogue, where architects and other professionals can share our experience. We have drawn on the experience of the following Madrid-based architecture firms that have succeeded in expanding their practice into the world outside Spain. Each firm was sent a form with a series of questions through which to build an offshore conversation, both in form and content. Austria, Belgium, Colombia, Italy, Portugal and Switzerland serve as case studies to provide a comprehensive ideal of the ecosystem of design competitions and how there are other models for practising the profession by means of this format.

Toni, Javi y Silvia

In the countries where you have expanded your firm’s presence, do you consider design competitions to be the base for the practice of the profession?

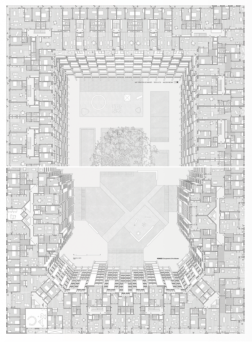

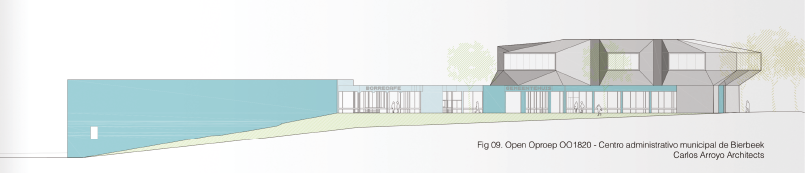

Carlos Arroyo Architects

arenas basabe palacios arquitectos

In Switzerland they’re essential for the evolution of thinking on architecture and urban planning, and they greatly influence the quality of the built environment. Not only that, but competitions in architecture and urban planning in Switzerland are internationally renowned for the exemplary way in which public contracts are awarded.

In Belgium, competitions are also an essential

pillar for practising the profession. Public works projects are very important in terms of volume, but private sector projects are also often subjected to open competitions, given that building rights, permits, building density, and even land ownership may be impacted by public quality control.

Quality control of public sector projects is essential in design competitions in Austria. This country has a long tradition of architectural design competitions, which is directly related to the importance of the public sector in housing construction. For instance, almost 50 per cent of homes in Vienna are social housing to a certain degree. In these cases, Vienna’s “housing fund” buys up a large amount of land, which it makes available to certain types of “public interest” developers and cooperatives to construct social housing. These have to compete with a project, and they’re chosen according to predominantly qualitative criteria. All homes that are built or retrofitted rely on project competitions, which prioritise the quality of the designs.

It can’t be said that architectural design competitions are the base for the architectural profession, but they do evidence a level of quality in the country’s architecture. The architect’s profession in Colombia is somewhat different to that of Spain, given that there are fewer professional competences there. In Colombia, the architect is commissioned with the architectural design and is responsible for this and coordinating the other technical disciplines associated with a construction project whose responsibilities lie with these engineers and not with the architect. Nor do architects have any civil or criminal liability at the project management stage, which is for the construction company.

Toni, Javi y Silvia

However, in the case of Italy and Portugal, the

importance of competitions in the practice of the profession is

similar to that found in Spain, isn’t it?

na Avenida de Belo Horizonte, em Setúbal. | Ignacio Senra y Elisa Sequeros

In actual fact, our Italian experience has been very brief – two competitions – but, paradoxically, very successful: one win out of two attempts. In Italy it’s an important part of practising the profession. Italian firms often take part, and it’s reasonable to say that they enhance the practice, without a doubt; but we wouldn’t be so bold to say that they’re the base for the practice. Milan is a special place that brilliantly combines Mediterranean poetics with Central European precision. We’ve known it for years, and it has been undergoing a profound revitalisation in recent years. As part of this process, many urban regeneration operations have been put in place as a result of architectural design competitions with results of a medium to high quality, although uneven. As always, everything depends on having a good jury.

The ideas competition (concençao) is still an omnipresent part of the practice in Portugal. However, our participation in architectural design competitions in Portugal have focused on housing projects organised by IHRU, a state government entity that develops social and affordable rental housing. These competitions are open to any European architect.

Toni, Javi y Silvia

Let’s speak about formats. What is the general structure

taken by competitions?

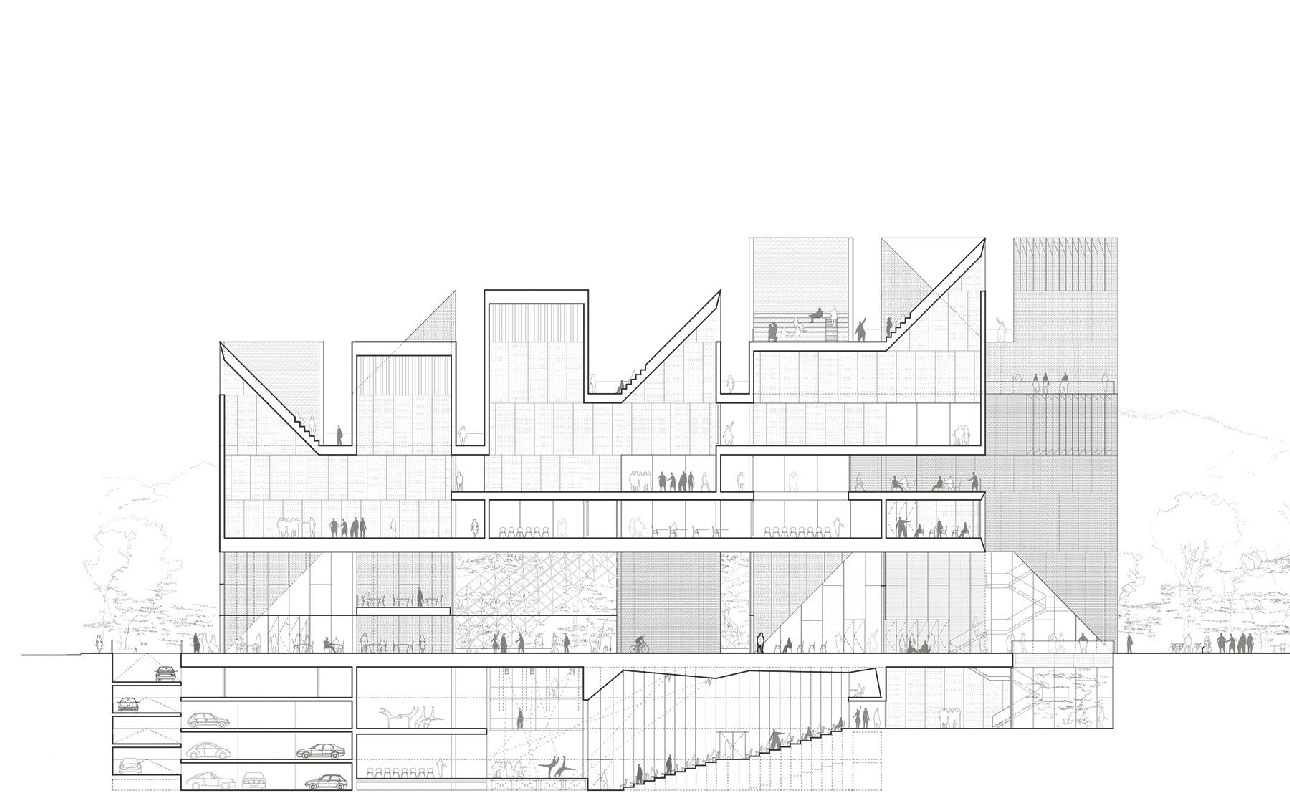

Fabbrica | FRPO + Walk + SD Partners

estudio_entresitio

Carlos Arroyo Architects

They work in a very similar way to how they’re held in Spain. Our experience was with a two-stage open competition. In our case, the first stage – which is unremunerated – had 58 entries, and they only announced the projects that made it through to the finals, whose average quality was good. Seven were shortlisted for the final stage, organised by Milan City Council and the Teatro alla Scala via the concorrimi.it website.

In Portugal it’s somewhat different from how they do it here [in Spain]. Currently, tenders aren’t allowed for design and build projects: by law, they have to be two separate tenders. Depending on the volume of construction, they give between three and six prizes, and the first prize is associated with the design contract for the specific building project. It’s also unusual to find the practice of auction-style tenders where the lowest architect’s fees are part of the process and quite often determines the choice of design in many cases. However, there’s a draft law on public procurement that will allow, as has occurred in Spain, a design and build project to be awarded to a single company or joint venture, leaving the drafting of the project to the construction company.

Architectural design competitions in Colombia work in a very similar way to how it’s done in Spain. There are open and closed, and public and private competitions, with or

without remuneration. In our case, we’ve taken part in a number of different open competition for public projects and were lucky to win first prize for the Museum of National Memory of Colombia (2015) and a third prize for the New District Cinematheque in Bogotá (2014), both in collaboration with Pacheco Estudio de Arquitectura as a local partner.

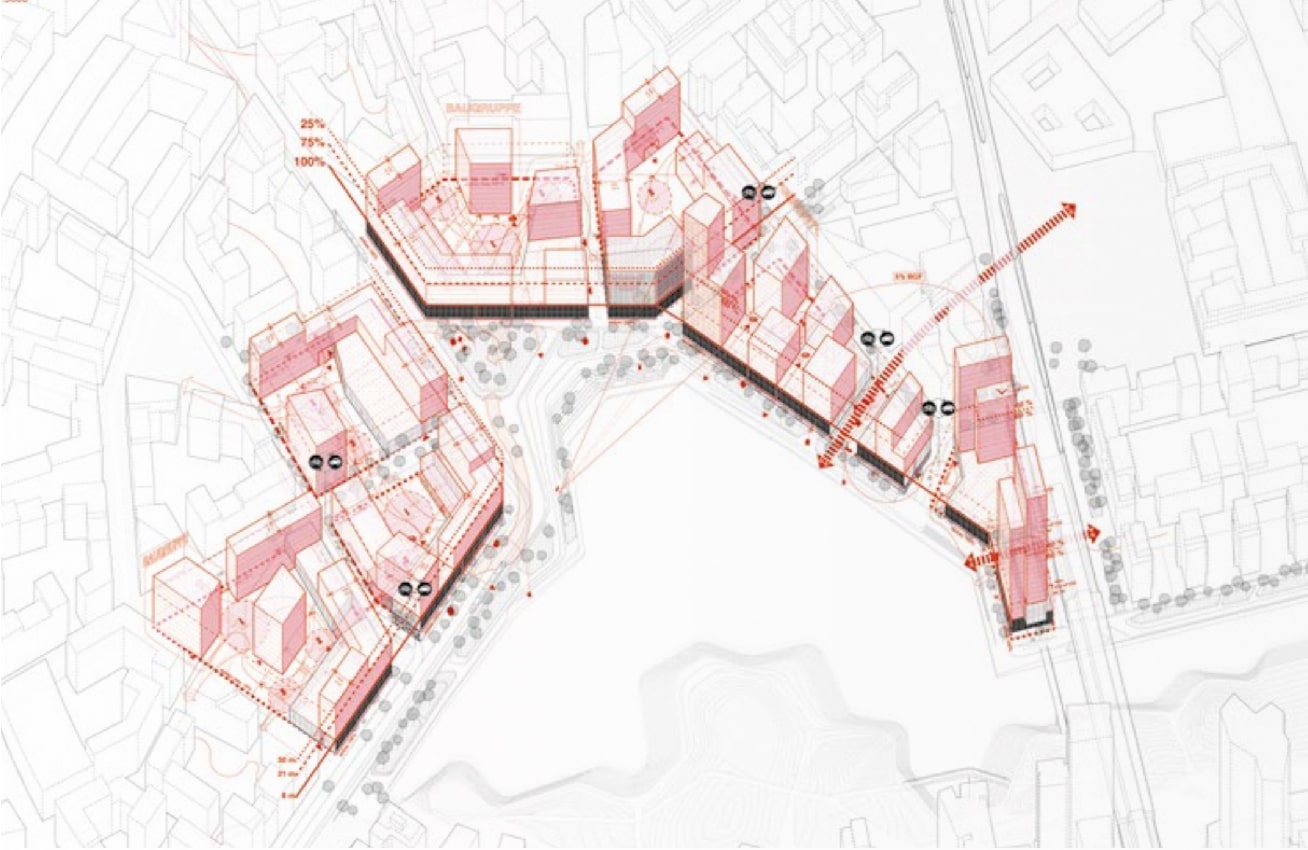

There are three types of procedures in Switzerland. Competitions can be open, ensuring a simple and efficient process, by selection, with a detailed study of all the merits of each interested firm, or by invitation. Each development company, whether public or private, defines the appropriate procedure and the number of selection stages. Competitions by

selection and by invitation restrict the number of designs, which guarantees remuneration for all candidates.

In Austria, both for urban planning and construction, it’s very common to have two-stage competitions, but in this case, the aim of this format is to reduce the unremunerated workload for the architecture firms. The first stage generally requires a single panel to be produced, with predefined content, and you aren’t even allowed to include overly elaborate material, such as realistic renderings. A varying number of candidates make it through to the second, remunerated stage, where the submissions tend to be a lot more extensive (between three and five panels in DIN A0 size). There tend to be a large number of main prizes and consolation prizes, sometimes as many as there are finalists. These competitions are often preceded by a qualifying stage in which technical and economic worthiness criteria are established, and as a rule, they require each team to partner with a landscape design firm.

Competition formats are quite varied in Belgium, depending on the institutions holding them and the aims of the project, but the two typical extremes in other places are practically non-existent here: there are hardly any competitions for the lowest financial proposal, and there are no unremunerated ideas competitions.