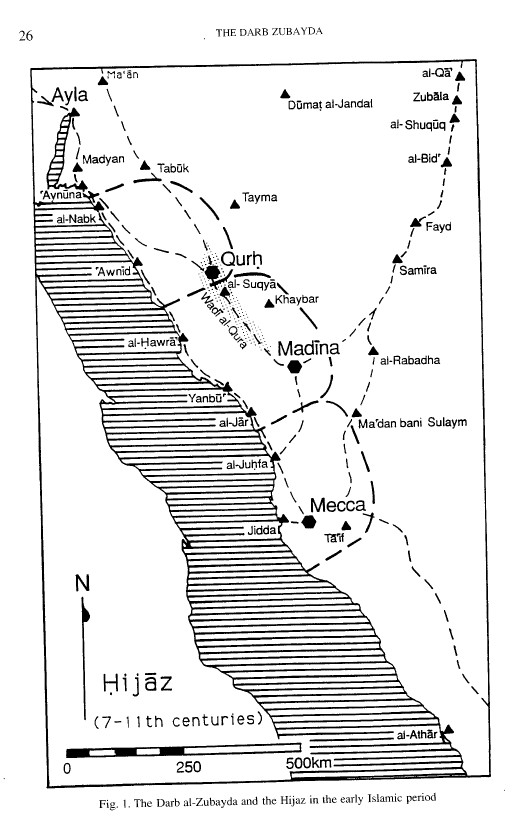

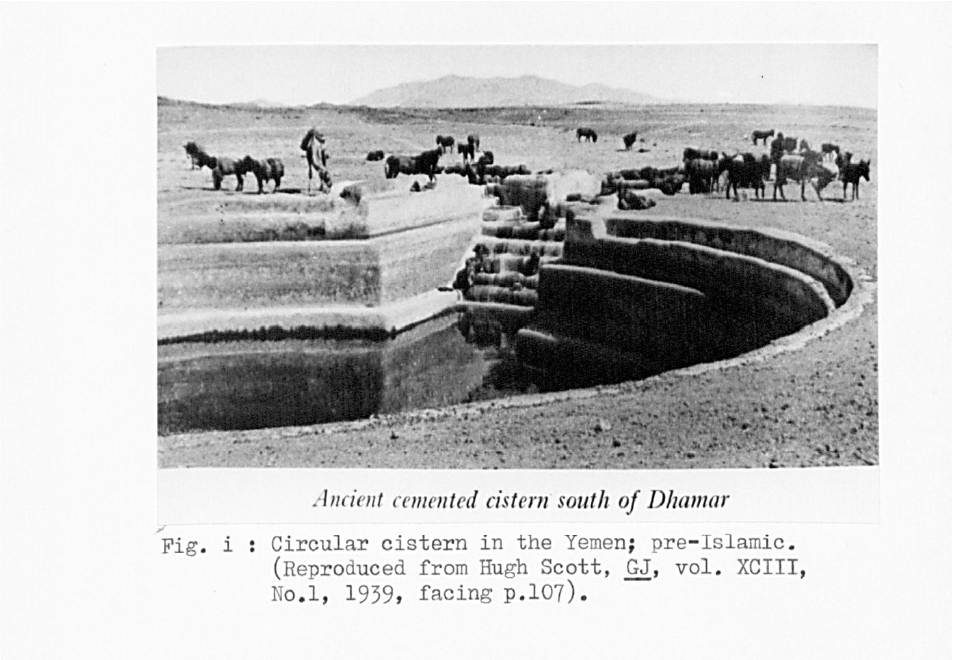

Zubaydah’s trail — a historic landmark and ancient international road to Makkah —invites us to reconsider architecture not as object, but as infrastructure of passage: responsive to terrain, climate, and the fragile needs of those in transit. Along these routes, architecture was never autonomous; it was inseparable from landscape, shaped by scarcity, wind, heat, and distance. Shade, orientation, access to water—each intervention was a gesture of adaptation, of survival, and ultimately, of hospitality. This climatic intelligence, grounded in local knowledge and collective memory, reveals a form of architecture that does not dominate the environment, but listens to it.

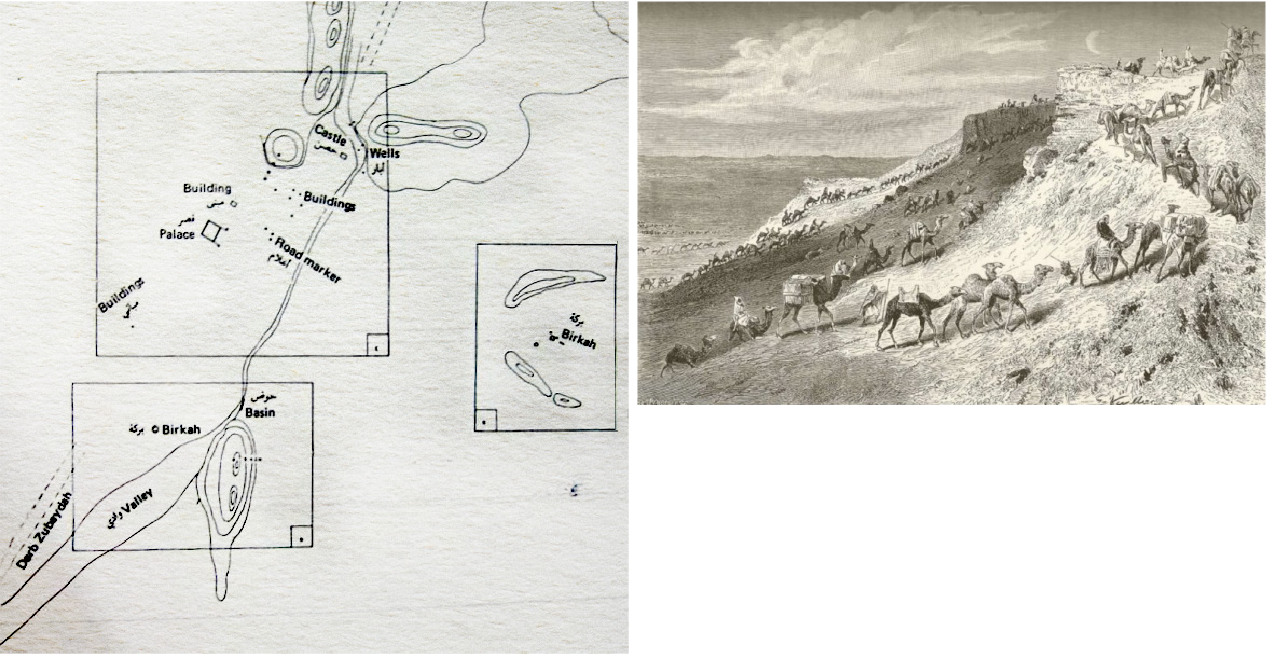

(Fig. 02)

Mao from the archaeological report by Salah Al-Halwa and Neil Mackenzie in 1399.

(Fig. 03)

Camel caraval travelling at night, depicted in an engraving by Gaston Vuillier, 1878-1879.

The journey itself becomes a spatial condition. Pilgrimage routes like the Darb Zubaidah offered not just physical continuity, but emotional calibration—where endurance, uncertainty, and transformation unfolded across both inner and outer landscapes. These trails stitched together distant geographies not only with stone, but with meaning.

The journey, then, is never merely geographic—it is bodily, emotional, temporal. To reach a destination after enduring the desert is to carry the imprint of the journey within.