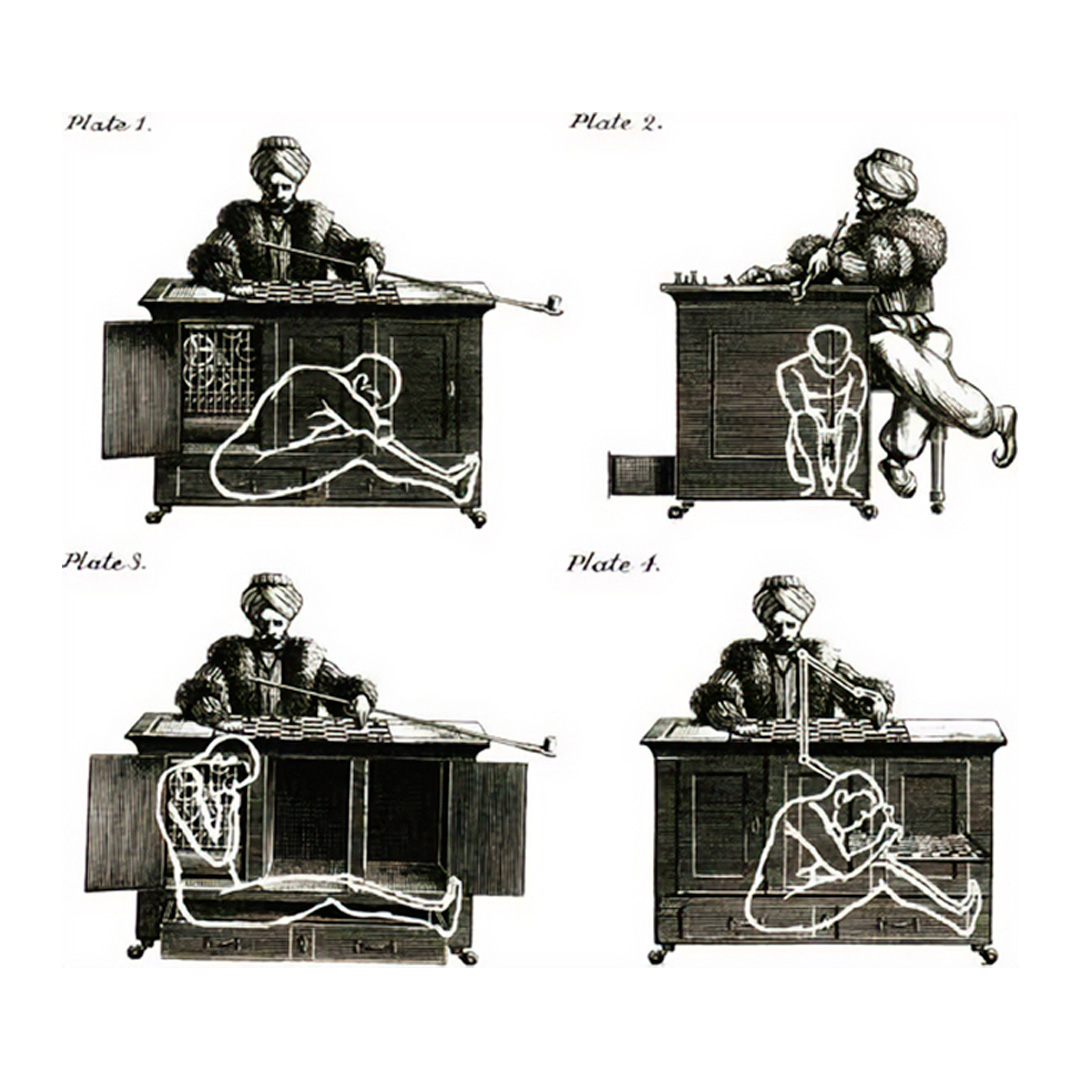

In 1770, a machine capable of playing chess with notable skill was built and remained operational for 84 years until it was destroyed in a fire. During that time, no one could prove the trick behind it. It was the creator’s son who revealed the secret years later: The automaton hid a human inside who decided and executed the moves.

Two centuries later, in 1997, world chess champion Garry Kasparov was defeated by a supercomputer designed to play based on brute computational force. Kasparov claimed that some moves could only have been made by a human operator.

In 2016, professional Go player Lee Sedol was defeated by an AI created by Google: AlphaGo.

Behind these three machines were humans interpreting code. Whether applying a chess player’s knowledge in real-time, programming possible moves, or predicting plays, the data informing each move had been collected, organized, and structured through human labor.

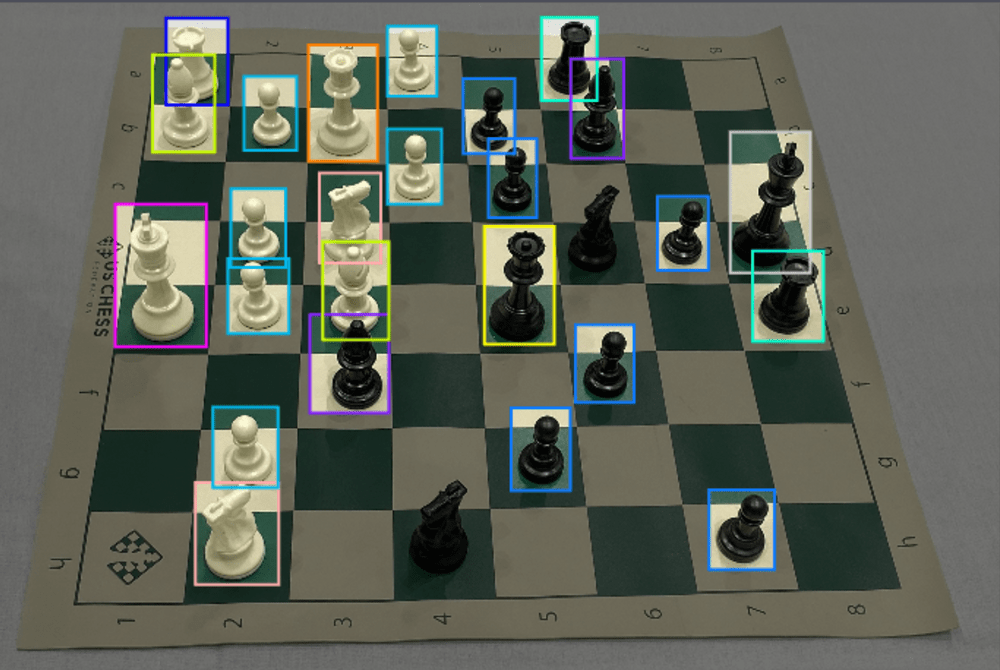

(Fig. 04)

Chess Pieces Computer Vision Project

Link: https://universe.roboflow.com/joseph-nelson/chess-pieces-new?ref=blog.roboflow.com

In 2005, Amazon launched a crowdsourcing service defined by them as “artificial artificial intelligence.” In this service, millions of micro-tasks necessary for training an AI are outsourced at an affordable price. Or, as they put it: “A global, on-demand, 24×7 workforce.” It was named Amazon Mechanical Turk, referencing the false automaton, and in the same way, it has humans doing what the machine cannot.

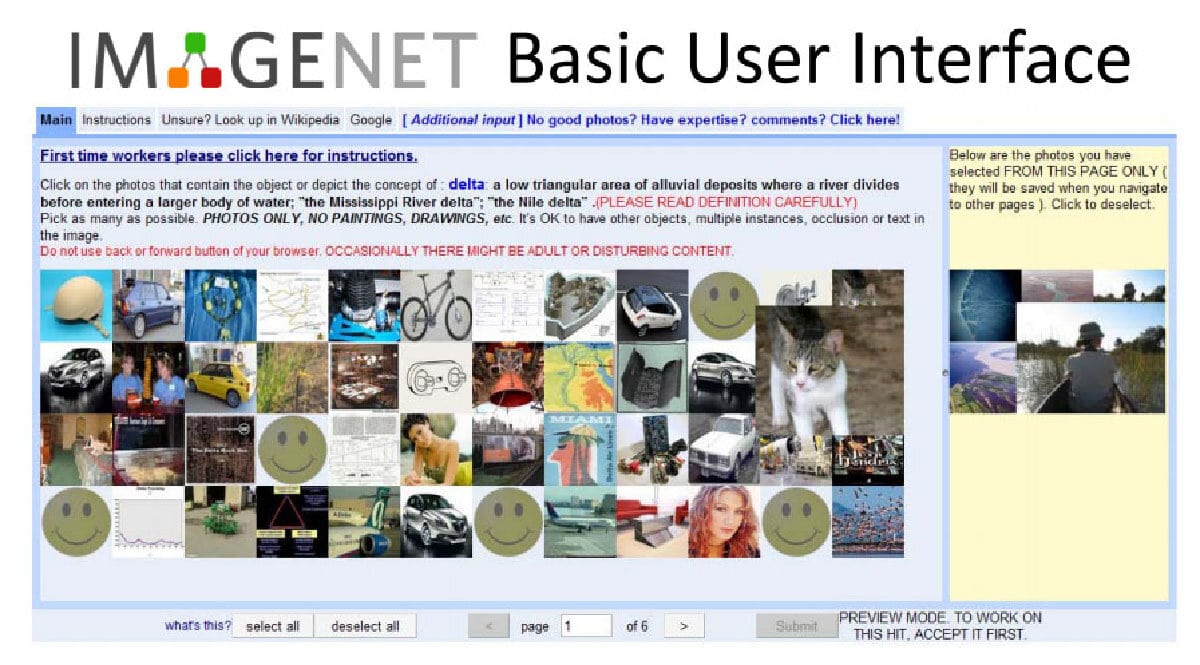

(Fig. 05)

Interface used by Amazon Turk Workers to label pictures in ImageNet. From Kate Crawford and Trevor Paglen, “Excavating AI: The Politics of Training Sets for Machine Learning” (September 19, 2019)

Link: https://excavatin.ai