Climate, once a shaper of customs, ways of doing, celebrating, praying, or working, is now just “average weather”—something checked from the sofa through a smartphone.

According to the OMS Europe report (2013) and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency report (2018), the average Western citizen spends 90% of their time indoors. We are called the Indoor Generation—a generation capable of artificially controlling indoor environmental conditions through meticulous management of temperature, humidity, and oxygen in order to maintain consistent air quality throughout the year. We are completely detached from the outdoor climate. We’ve grown up, been educated, spent our free time, and moved through hermetically sealed, fully conditioned spaces, disconnected from external weather conditions. Unlike our grandparents and their ancestors, we know nothing about the climate. And yet, it is our generation that is being asked to shoulder the burden of fighting and overcoming climate change. A point of no return is set: the year 2050. A limit goal: +1.5ºC. Under these milestones lies an unprecedented generational responsibility, a psychologically overwhelming individual pressure. Uncertainty and anxiety arise:

Is our generation ready to face this challenge?

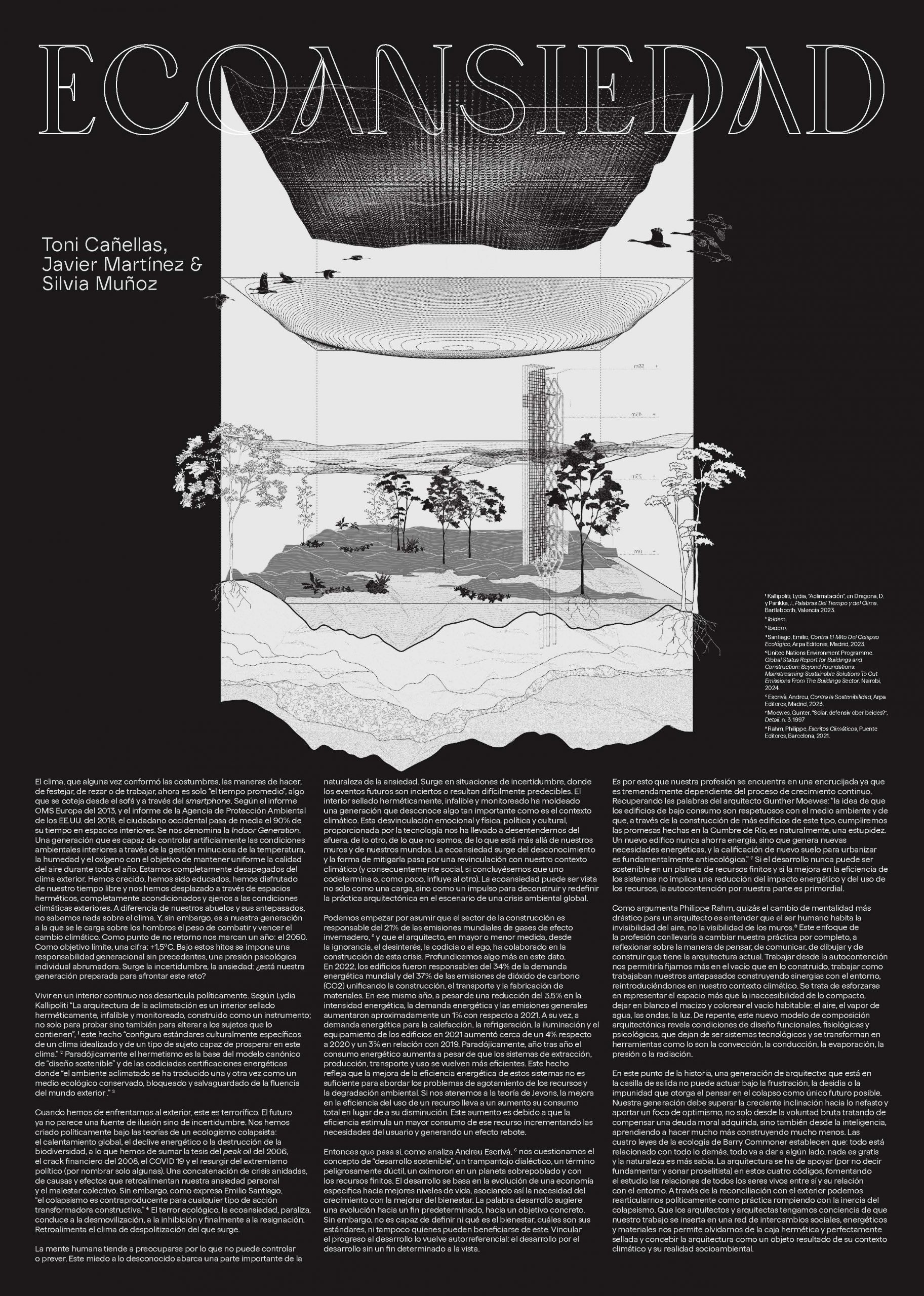

Living in a continuous interior disempowers us politically. As Lydia Kallipoliti states, “The architecture of acclimation is a hermetically sealed, infallible, and monitored interior built as an instrument—not only to test but also to alter the subjects it contains.” This condition “shapes culturally specific standards of an idealized climate and of a type of subject capable of thriving in that climate.” Paradoxically, this hermeticism is the foundation of the canonical model of “sustainable design” and the coveted energy certifications where “the acclimated environment has been repeatedly translated as a preserved ecological medium, locked and safeguarded from the flux of the outside world.”

When we must face the outside, it becomes terrifying. The future no longer seems a source of hope but of uncertainty. We were raised politically under the theories of collapse-driven environmentalism: global warming, energy decline, biodiversity loss, along with the 2006 peak oil thesis, the 2008 financial crash, COVID-19, and the resurgence of political extremism (to name just a few). A chain of nested crises, of causes and effects, that reinforce our personal anxiety and collective unease. However, as Emilio Santiago notes, “collapse-ism is counterproductive to any kind of constructive transformative action.” Ecological terror—eco-anxiety—paralyzes. It leads to demobilization, inhibition, and ultimately resignation. It feeds the depoliticized climate from which it arises.

The human mind tends to worry about what it cannot control or foresee. This fear of the unknown forms a significant part of the nature of anxiety. It arises in situations of uncertainty, where future events are either unknown or hard to predict. The hermetically sealed, infallible, and monitored interior has shaped a generation unaware of something as fundamental as the climatic context. This emotional, physical, political, and cultural detachment—enabled by technology—has led us to disengage from the outside, from the “other,” from what we are not, from what lies beyond our walls and our worlds.

Eco-anxiety arises from ignorance, and the way to mitigate it is through reconnection with our climatic context (and consequently social context, if we conclude that one co-determines or at least influences the other). Eco-anxiety can be seen not only as a burden but as a driving force to deconstruct and redefine architectural practice in the face of a global environmental crisis.

We can begin by acknowledging that the construction sector is responsible for 21% of global greenhouse gas emissions, and that architects—whether through ignorance, indifference, greed, or ego—have contributed to building this crisis. Let’s delve further into the data. In 2022, buildings accounted for 34% of global energy demand and 37% of CO₂ emissions, combining construction, transportation, and material manufacturing. That same year, despite a 3.5% reduction in energy intensity, overall energy demand and emissions increased by about 1% compared to 2021. Furthermore, energy demand for heating, cooling, lighting, and equipment in buildings rose by nearly 4% from 2020 and 3% from 2019. Paradoxically, year after year, energy consumption increases even though systems of extraction, production, transportation, and use become more efficient. This indicates that improving energy efficiency alone is not enough to address resource depletion and environmental degradation. According to Jevons’ Paradox, increased efficiency in the use of a resource tends to lead to greater overall consumption of that resource rather than its reduction. This increase stems from efficiency enabling greater use, expanding user needs and causing a rebound effect.

So, what happens if, as Andreu Escrivá analyzes, we question the concept of “sustainable development”—a rhetorical sleight of hand, a dangerously flexible term, an oxymoron on an overpopulated planet with finite resources? Development is based on the evolution of a specific economy toward improved living standards, thus linking the need for growth with enhanced well-being. The word “development” suggests a progression toward a predetermined end, a concrete goal. However, it fails to define what “well-being” is, what its standards are, or who benefits from it. Linking progress to development makes it self-referential: development for development’s sake, with no clear end in sight.

That’s why our profession stands at a crossroads, deeply reliant on continuous growth. In the words of architect Gunther Moewes: “The idea that low-energy buildings are environmentally friendly and that by building more of them we will fulfill the promises made at the Rio Summit is, naturally, nonsense. A new building never saves energy; it creates new energy needs, and the designation of new land for development is fundamentally anti-ecological.”

If development can never be sustainable on a planet with finite resources, and if efficiency improvements don’t imply a reduction in energy impact and resource use, self-restraint on our part becomes essential.

As Philippe Rahm argues, perhaps the most drastic mindset shift for an architect is realizing that human beings inhabit the invisibility of air, not the visibility of walls. This reorientation of the profession would completely transform how we think, communicate, draw, and build. Working from self-restraint would encourage us to focus more on voids than on solids, to work as our ancestors did—building synergies with the environment, reintegrating ourselves into our climatic context. It’s about striving to represent space rather than the impenetrability of mass, leaving the solid blank and coloring the habitable void: air, water vapor, waves, light. Suddenly, this new architectural model reveals functional, physiological, and psychological design conditions that are no longer technological systems but tools—convection, conduction, evaporation, pressure, radiation.

At this point in history, a generation of architects just setting out cannot act from frustration, apathy, or the impunity granted by thinking of collapse as the only possible future. Our generation must overcome the growing inclination toward the disastrous and bring a sense of optimism—not only from sheer will, trying to pay off a moral debt, but also from intelligence: learning to do much more by building much less. Barry Commoner’s four laws of ecology state: everything is connected to everything else; everything must go somewhere; nothing comes free; and nature knows best. Architecture must be based (not to say founded, to avoid sounding proselytizing) on these four principles, promoting the study of relationships among all living beings and their environment. Through reconciliation with the outside, we can politically rearticulate our practice, breaking the inertia of collapse-ism. For architects to understand that our work exists within a network of social, energetic, and material exchanges allows us to move beyond the sealed box and to conceive of architecture as an object resulting from its climatic context and socio-environmental reality.